If you like this article, read more about Milwaukee-area history and architecture in the hundreds of other similar articles in the Urban Spelunking series here.

Google the phrase "survivalist bunkers" and you’ll get a vast array of results, including articles about the phenomenon, websites for companies that build them and some rather astonishing photos of extremely elaborate ones – sometimes called luxury bunkers – that double, at least until the apocalypse, as wine cellars, man caves, rec rooms and more.

Today’s luxe bunker is a descendant of an earlier, starker Cold War-era craze: the residential fallout shelter.

As the Cold War raged, as fears of nuclear war terrified, as Khrushchev railed at Nixon, pounded his shoe on the table and vowed to bury the United States, Americans sought safety, leading to community fallout shelters being built and stocked with fresh water, toilet paper and other necessities.

Many also spent big money to build their own shelters at home.

While you’re on Google, search "1960s fallout shelter" and you’ll find lots of articles about homeowners unexpectedly finding old bomb shelters behind walls in their basements and buried in their gardens.

By early 1960, more than two-and-a-half years before the Cuban Missile Crisis amped up Cold War fears, the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote about proposed tax deductions for homeowners who spent money to build their own fallout shelters, and soon after classified ads began to appear in the local newspapers advertising masonry firms that listed fallout shelter construction among their services.

But the trend wasn’t a local one, of course, at the spring 1960 American Institute of Decorators at the Home Show, an exhibit offered a glimpse into "The Family Room of Tomorrow," a family fallout shelter that was designed to serve as an extra room for families to use regularly, but that was constructed to serve as a shelter.

According to an article in the Sentinel about the exhibit, "done in cooperation with the U.S. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, a wide variety of ‘shelter’ family rooms will be shown. This one incorporates a dozen living factors including entertainment, exercise, sleeping room for four, storage space, cooking units and water."

It appears that many shelters were built in Milwaukee.

In January 1961, the morning newspaper reported on a survey conducted by the Milwaukee Civil Defense office, which sent out 103,000 questionnaires and received 66,048 replies.

The results showed that at least 3,004 City of Milwaukee homes had family fallout shelters.

"The figure is much higher than expected but far lower than it should be," the paper noted the CD office as saying. "Milwaukeeans are more civil defense conscious today that ever before, but they are a long way from being adequately trained and prepared to cope with a sudden major disaster – name an attack."

Interestingly, the 11th Ward had the most shelters with 354 and the 20th Ward had the fewest with 11. Older folks were more likely to build shelters, according to the survey, which added that 46,933 persons said they, "didn’t know under which conditions they would build one. Of those, 576 said they would build if they could finance the cost without a loan."

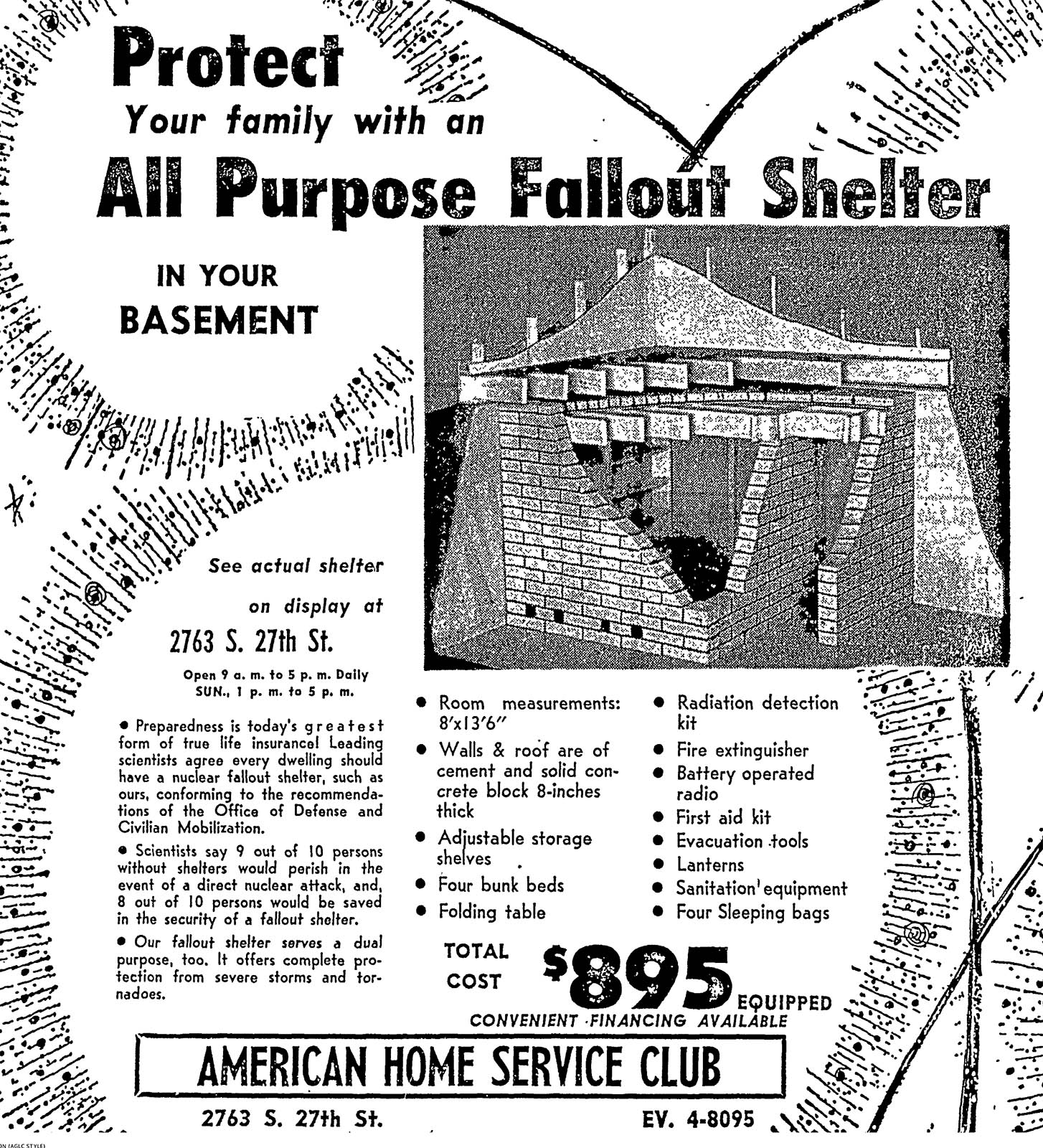

By this time, shelters were big business and display ads by contractors and realtors boasted of shelters.

That February, an ad for Jordan-Jefferson Inc. Realtors said, "this home has a full basement and an added feature in that we have included a fallout shelter; if you have never seen one it would pay you just to view the shelter and ask questions."

Residential real estate classifieds routinely listed fallout shelters among the amenities of properties for sale.

In April, there were even ads for built-it-yourself shelters, and in August, M&I Bank had a large ad that included this: "To cooperate with the Civil Defense Program, Marshall and Illsley will make loans to cover construction of a home fallout shelter. A shelter can also be used for storage, a fruit cellar, playroom or other purposes. Plans are available from Milwaukee Civil Defense Administration, 105 N. Water St."

All of this must’ve hit home with Vina Osborn, widow of William B. Osborn, a real estate and insurance man, who lived on the city’s west side with her adult niece Kathleen Clark in a Colonial style home the Osborns built in 1940 (and would remain in until the early 1970s).

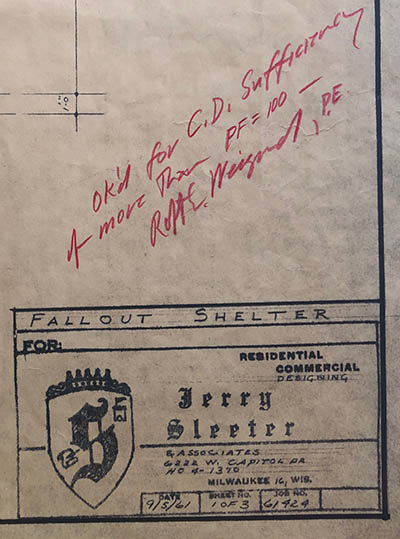

In 1961, Osborn tapped local designer Jerry Sleeter to design a shelter for the house.

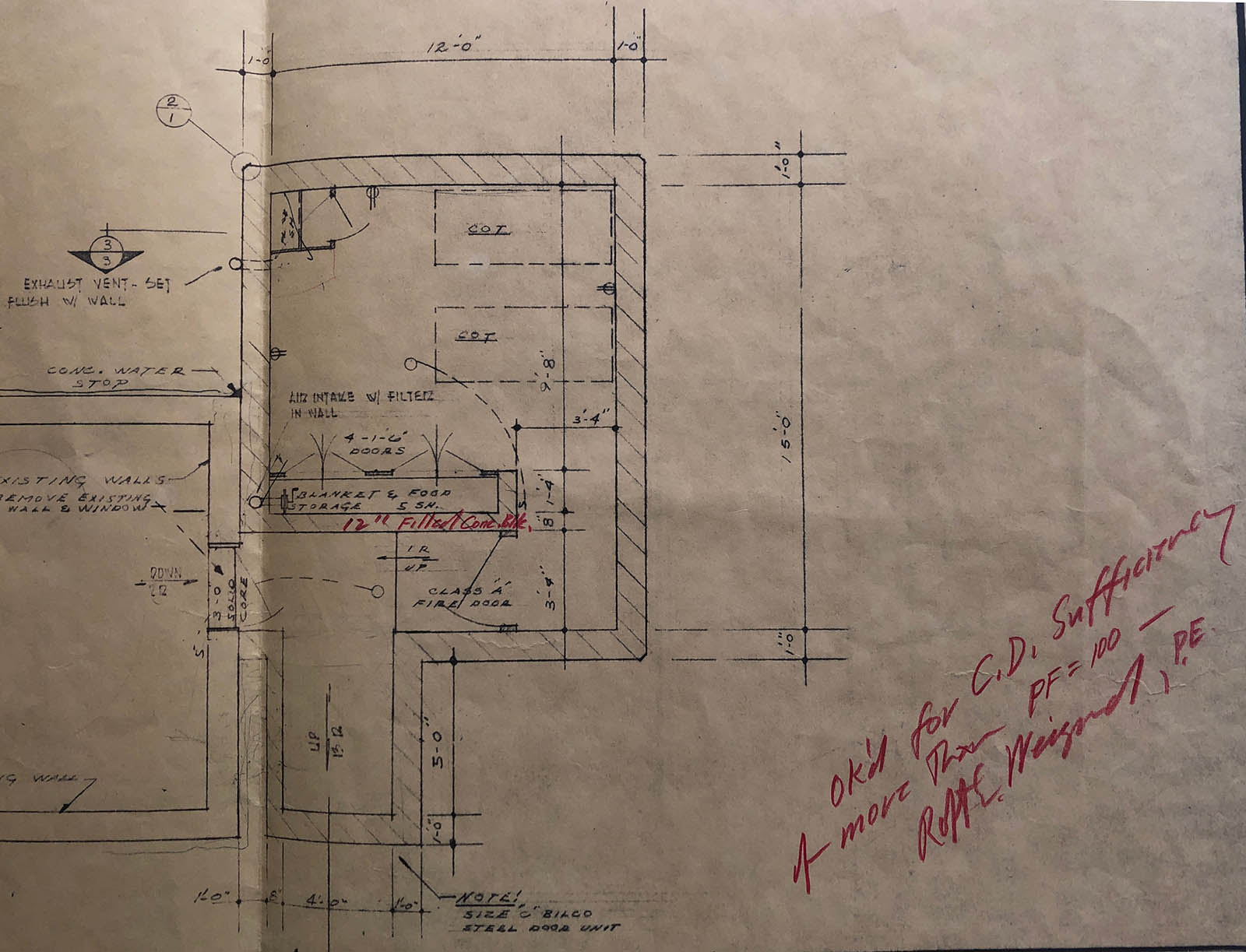

The backyard of the home must’ve been excavated by Mollgaard Company, a contracting and real estate company, who then built a concrete shelter 12 feet wide by 15 feet long and opened the foundation wall to offer a connection into the basement.

The work, begun in September, cost Osborn $2,000, plus whatever she paid Sleeter for his design work.

Drawings show the shelter buffered from the house by a solid core door at the junction and another class A fire door a little further into the shelter access.

Two cots as well as a blanket and food storage area are shown, too, along with a small corner area with a door that, perhaps, served as a water closet.

Air intakes with filters were built into the walls.

An interior wall of filled concrete block is 12 inches thick and the exterior walls, of what appears to be poured concrete, are shown to be thicker.

Fortunately, friends currently own this house, though they’re selling (to other friends ... Smallwaukee!), so I got a peek inside recently.

These days, the corner water closet is gone, but some pipes still emerge from the wall in that corner. The doors are also gone.

The air intakes up in the backyard – pipes about four feet tall with covered openings at the top (pictured below) – still exist, but back downstairs there are no cots and no more doors. A sump pump has been added.

The outgoing homeowners used it for additional storage.

The new ones have grander plans.

"The whole house is great, but the fact that it has a bomb shelter has been one of the stand out bragging points to our friends," one of them tells me. "It's quirky and functional, adding extra space to the basement and, let's be honest, with the way 2020 is going there are days when an underground hideout sounds kind of appealing.

"Friends have joked that we should make it into an Escape Room or a cigar lounge, but my partner is really excited about the potential for a speakeasy with a secret door. Maybe a bookcase? Maybe a walk-in freezer? With everyone focusing on home projects at the moment, it only feels natural for our first home project to be a secret bar in our underground bunker."

These uses echo how many of the shelters were used once the craze ended.

Into the 1970s, realtors still advertised homes with shelters and there were ads boasting of the benefits of shelters, including as protection from weather threats like tornadoes and hurricanes. But, the moment had passed and shelters were already viewed more as novelties than protective spaces.

Interestingly, the number of public shelters had continued to grow, from about 1,000 in 1967 to as many as 1,285 by 1975.

A 1972 Associated Press article from Newark bore the headline, "Shelters fall out of style in the US."

"Mrs. William Weiss keeps her Bordeaux wines there," the story read. "Mrs. Aaron Bernstein’s children use it to store fish tanks. Raymond Lauer finds it’s a great place to relax and cook a quiet dinner. They have all found a new use for an old fad: the fallout shelter.

"In the early 1960s homeowners fearing a nuclear holocaust brought in the bulldozers, tore holes in their backyards and built private bomb shelters. Ten years later, a spot check of owners around New Jersey show most of the shelters have been converted to wine cellars, dens, tool shops or children’s playrooms.

"Some persons who built the shelters were reluctant to talk about them. Others said their shelters were sealed several years ago. Most shelters were built during the Cuban missile crisis era 10 years ago this autumn. Contractors did a booming business but as the urgency of protection fell off, so did the fallout shelter trade."

Three years later, a Journal staffer added, "Of all home remodeling projects, few had a more meteoric rise and fall than the bomb shelter. Talk of them was all the rage in the late 1950s and early 1960s, their appeal fanned by the cold war flames and magazine covers of Nikita Khrushchev in front of mushroom cloud backdrops. But the idea of a basement or backyard fortress against nuclear attack bombed, so to speak, within a few years. As initial hysteria subsided, a crisis activated people lost interest."

That article suggested there were maybe only 12 or 15 ever built in the city, which is vastly different than the Civil Defense survey number of the early 1960s. But, as the writer suggested, it was impossible to really know, as the Civil Defense office didn’t keep records of them.

Interestingly, four of the shelters the writer found in Milwaukee were "still stocked and ready."

One homeowner who bought a house with an existing shelter in Shorewood, told the paper, "It’s ridiculous. If a bomb would fall we wouldn’t survive in a thing like that. It would be a horrid place to live."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press. A fifth collects Urban Spelunking articles about breweries and maltsters.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has been heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.

%20copy.jpg)