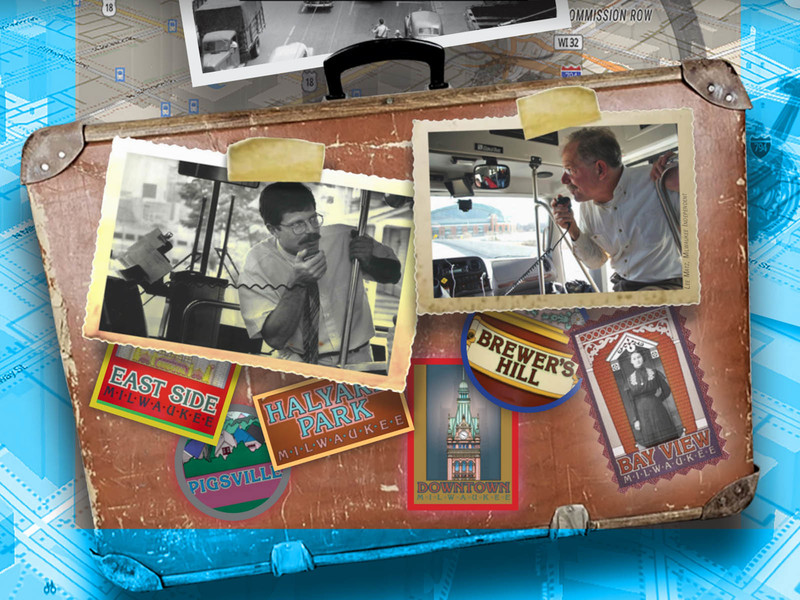

If his previous work cataloging the history of Milwaukee didn't make South Side native John Gurda a hometown celebrity, then surely his sprawling and impressive "The Making of Milwaukee" and its accompanying TV series did.

Now, he is, without a doubt, recognized as the living memory of Milwaukee, especially now that the formidable Frank Zeidler has left us.

Gurda took some time away from his latest project -- a history of Jewish Milwaukee -- to answer our questions and we asked him about how he got into the history game and more in this edition of Milwaukee Talks.

OMC: Where does your love of history come from?

JG: I really did not get into history until after college. I had two brothers who couldn't care less, who were raised by the same parents in the same household in the same neighborhood with all the same influences. I'm not sure what it is.

OMC: What is your Milwaukee background? Where did you grow up?

JG: I was raised on South 34th Street near Jackson Park until I was 8, and then moved out to Hales Corners. Graduated from high school and then moved back into town after college. My dad's Polish, mom's Norwegian ... their backgrounds. My grandparents had a hardware store on 32nd and Lincoln for 50 years, from 1915-'65.

So that was kind of my world, you know? Even when we became suburbanites, we were still spending a lot of time on the old South Side. We'd go to the Folk Fair every year, there was Polish Festoons at Christmas, we'd go to my mom's farm in summers. So there was, if you wanted it, you could sort of relate to the traditions ... and, I did, and my brothers didn't, especially. It just struck some sort of a native cord.

OMC: When did the history come?

JG: When I really got into history was after college when I graduated as an English major from Boston College. I came back to Milwaukee and -- this is 1969 -- wanted to write and (was) interested in being a poet, but all of those jobs were taken. There wasn't much going on there.

I ended up working for three years at a youth center called Journey House, which is still there. It's been there for 40 years. Working with, at that time, largely Anglo -- some Latino population coming in. We were just a shoestring operation -- I think we had six full-time staff and the operating budget was $45,000 plus the building we were renting and supplies. We were just living on air. So we began to do some fundraising (for a project) to examine the neighborhood (which I did) just instinctively, both in terms of where it was and where it came from. I don't know if we tossed a coin or what, but I did the history portion. It was just ... the light bulb comes on, and you hear the chorus.

OMC: Did you go back then and study history formally?

JG: Not for a while. That led to a publication -- little ... very primitive (one) -- called "The Near South Side: A Delicate Balance," fearlessly titled. That led to a job doing research for United Way Project that was doing neighborhood-based needs assessments. When that was done, I was laid off.

Just because I was fascinated, I did a little pamphlet about South Side history which is was my family -- my roots. I'd come across things. I'd be going through the County Historical Society archives and my great uncle, who was a real hero to my dad and therefore to me was the first Polish captain of the second precinct. I'd find references to him. I found correspondence in the Polish ethnic file on my dad, being the secretary of a Slavonic Society at UW-Madison back in the 1920s, so it was sort of personal.

OMC: Is that how you found the early projects you worked on? Did the sort of come to you in that sense -- out of personal relationships?

JG: The "Separate Settlement" project came because I wrote it absolutely on my own with no expectation of being published -- no one funding it, no one sponsoring it, and the United Way published it. They read it and said, "Whoa, that's kind of interesting." Nobody was doing neighborhood stuff back then. That came out in 1973 or so ...‘72-‘73. So yeah, it was kind of the blend of this is a really interesting history in its own right, but I'm part of it. It's my story as well as the city's story. And that led to a project in Waukesha County, again for United Way. It was what they called the "informal survey," which was going around and talking to people. And it was ...

OMC: Was it written as oral history in a sense?

JG: No, it was more journalistic, and it was just -- if I read it now -- the publication was another great title, "Understanding Waukesha County." There are 16 townships in Waukesha County and each one -- obviously Menomonee Falls is out by itself, but then out in Merton you've got a couple of villages as well as a township, and I think I had three weeks to do each township, and that meant historical research, interviewing people, doing some numbers and then writing a sketch of it.

I put probably a couple thousand miles on the car, and one of the guys in the project, an old friend, gave me a memo pad that read "From the Dashboard of John Gurda." It was indefensible research -- it was just crap. On the fly. Pretty basic stuff.

OMC: How did you parlay this then into a career? Was that a choice you made consciously?

JG: I was following my nose, and I had no real plan and honestly no real faith in how this could last. I'd been doing it pretty much full time or writing during layoffs. There's not much money involved here. About 1976 I realized that this could be work; this could be something as I do as a career. I had a serious lack of skills; a serious lack of background, so I knew I had to go to grad school.

UWM was the obvious choice, financially, and in terms of convenience. I talked about history, sociology, urban affairs and geography, and ended up going to geography. They had a really strong geography department and what I was doing was -- you could do MA or MS -- I did MA on the cultural side, and what I was doing was historical geography. What I was doing was neighborhoods, so I ended up getting a Masters in cultural geography and my thesis was on Jones Island, which was just fascinating stuff.

OMC: At UWM at the time, was there an understanding of the importance of the focus of some hyper-local history at that point?

JG: It was beginning, I think. It was long before the Milwaukee idea and those sorts of locally-applied things, but there was a strong urban geography staff there, and what better place to study the urban area than the urban area you're in. So there was a lot of Milwaukee stuff going on. People were doing topics -- thesis and dissertations -- on Milwaukee topics. So, no, it wasn't especially cutting edge, but it was still relatively early for doing that locally based stuff.

OMC: Do you have a moment you can look back on and say, this is when it started for you, a sort of official, legitimate, respectable career?

JG: Sure. Where it began to be more real, more sustainable - I graduated from the geography program in 1978 and a whole lot of my career has been circumstance and luck. Just good fortune. There was a program starting at UWM called the Milwaukee Humanities Program, and it was funded by The National Endowment for the Humanities and basically -- they had 400 grand to look at the city from the point of view of the humanities: literature, religion, history ... and it was pretty free-form. And I got hired as associate director or something. We were able to pick our own topics, and I said, ooh, neighborhoods. We were thinking in terms of an encyclopedia of Milwaukee neighborhoods and we knew -- we had two years of funding -- we knew this could be a sort of a prototype, something that would last on its own, but we wouldn't finish it. There was a senior component; there was a TV show, there was a film; there were books on women -- so it was really kind of somewhat motley.

JG: No, the encyclopedia did not, but I did Bay View and the West End, and "Bay View, Wisconsin" came out in '79. It was published by -- the copyright is held by the UW Regents. And "The West End," which was Concordia, Pigsville and Merrill Park on the West Side, and a guy named Tom Tolan began the history of Riverwest that he finished in May -- his was not published until about five years ago, so those were the three. And that's about as far as it got. ... They were short, "Bay View" was 100 pages and "West End" was 106 pages.

OMC: Was "The Making of Milwaukee" in a sense a culmination of all of the things that came before? Would you have done "The Making of Milwaukee," if you hadn't led up to it with this kind of path?

JG: No. And where that began was -- by that time -- so say it began in '72, when I began to write stuff about Milwaukee, and it wasn't until 1994 or ‘95 when I began to work on "The Making of Milwaukee," so I had 20-plus years of bits and pieces. And I felt both the psychological need, and I felt there was a not a market need but a community need for something that was weightier, more comprehensive -- the whole story, not bits and pieces.

OMC: Did you always want to do that kind of book?

JG: No. It was hard.

OMC: That's why I wondered if it would be an audacious idea to say to yourself at some point, "I'm going to write what will be, at least for a little while, or maybe for a long while, the definitive history of the city"?

JG: It was intimidating. I spent four years on that project. I can recall living in Bay View and going downtown to research and just seeing the skyline of the town, which is not exactly overwhelming, but it ... we're a big city, and thinking, "I've got to tell the story of all this." And feeling, like, how in the world ...

OMC: Not to mention all of the fingers that radiate out from that.

JG: Right. How do you do that?

OMC: Do you have any regrets about it afterward?

JG: I've gotten a couple more swings. It's in its third edition now, which is more an update.

OMC: So, you've been able to go back and tinker a little.

JG: I've tinkered a little: added pictures that we've found -- wonderful photographs that we didn't have the first time around in 1999. But, no, I think it's a pretty solid piece of work.

OMC: You've become a local celebrity, which not many historians can say. "The Making of Milwaukee" probably cemented it, huh?

JG: Yeah, and the TV show. The recognition from people who don't necessarily read -- sort of channel surf and say, "oh, that's interesting."

OMC: Do you think there is anyone else in town doing the kind of work you're doing?

JG: Boy, Harry Anderson, the retired director of the Milwaukee County Historical Society had done research on the Bund during World War I and World War II, and I don't know if he plans to publish or not; Steve Avella, you know Steve, he's in the Marquette history department, he's updating his book on the Archdiocese, which is a pretty sizeable piece of work. A lot of the Arcadia stuff ...

It would be nice to have more. The Arcadia stuff, like Frank Alioto's book on Brady Street ... it's wonderful to have it collected between two covers with a photographic portrait of an area; they're very useful. But, they're limited in terms of the scope.

OMC: Tell me a little bit about what you're working on at the moment, if you can.

JG: Just in the production for history of Milwaukee's Jewish community, it's going to be called "One People, Many Paths", and it's a history of Jewish Milwaukee. The manuscript was finished about a month ago and we're gathering photos and hope to be out by November. That's been really interesting. It's been my main project for the last year and a half or so. ... And there hasn't been one on the Jewish community since about 1963 - a Rabbi named (Louis J.) Swichkow turned a dissertation into a book and it was well done -- very helpful. Very academic, quite dry. This is a stronger narrative book.

JG: Honestly, no, Bobby, there isn't a ... "The Making of Milwaukee" will be I think the -- that's probably the most ambitious thing I'll do. That was a lot of work. And I'd like to keep that up to date, so ...

OMC: So you intend to keep new editions as long as you can.

JG: Right. The last one came out six or eight months ago, and nothing's changed. Tom Barrett is still in office and Gwen Moore ... a contemporary can read it and say, yeah, I still recognize this. But that'll change, obviously. But I'd like to keep that up to date.

There are some, as I think about a more leisurely pace, the projects that aren't necessarily Milwaukee-centric, what's happened to blue collar workers as the economy has just absolutely transmogrified is really interesting to me. The trajectory of the Baby Boomers over time is really interesting.

OMC: How is Milwaukee going to get out of this economic situation?

JG: I think it's been a mixed bag for a long time. Back in the early ‘80s we lost a quarter of our manufacturing jobs. It really sandwiched the traditional base, but we didn't lose as much as Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland ... it's not the best company to be in, but there's a lot of comparable suffering in the older industrial cities of the north.

Milwaukee, relatively speaking, has had less erosion than some of those other cities, and the way out, I'm not sure and I'm not sure anybody is. I applaud the water initiative for a time Milwaukee, like a lot of other northern cities, are kind of chasing "high-tech," let's be Silicon Valley, but we can't all do that. Something comes out of it; something more organic that comes out of your strengths is a lot more profitable and a lot more practical.

OMC: Well we've had this long relationship with water.

JG: That's why we're here.

OMC: Right. Do you think there's other old ideas that Milwaukee will need to reconsider to get to the future, like light rail? I mean, things that we had that we didn't see the value in?

JG: My own feeling is that Milwaukeeans don't feel enough pain to create a real groundswell of demand for light rail. It could really help the city in terms of focusing the development and bringing energy to the heart of town, and I'm not sure what's going to happen but now that that federal money has been released, that could be kind of a down payment. More than a down payment -- it could be more of a catalyst for a more ambitious system. I'd like to see it, but when you're in a town that you could park all day downtown for $2.25 ... there isn't enough pain. Chicago obviously would be dead if they didn't have a light rail system.

OMC: Do you think there's some way to resuscitate the old guys, would they recognize it if they came back to the city? Obviously there is change that's happened everywhere in 100 years, but is there still a spirit, a feeling about the city that they would recognize? Or would it be completely foreign to them?

JG: I think if you went back as far as Juneau and Kilbourn, they'd be like, whoa, they just couldn't relate to the technologies to begin with. I think the more recent touchstone, we're talking 100 years, is the rise of municipal socialism here in Milwaukee. Frank Zeidler died three years ago, and ...

OMC: ... which is an incredible thought when you think about how far back into Milwaukee history he reaches.

JG: Yep. And he saw the changes and he was someone who was determined not to live in the past. He would comment, stay engaged, stay involved in what was going on. The whole Hoan years (1916-'40) early on, there was a sense that we were all in it together and it was easier to be in it together when you had a very working class population that was largely European ethnic. So there are a lot of differences as you know, with the Italians in Bay View vs. the Italians in the Third Ward; the Poles on the South Side and Germans on the North Side.

OMC: Do think the divisions were more or less severe than the divisions we have now in terms of segregation?

JG: I think it's so hard to compare. It's hard to see one time in the context of another. It's dangerous. If we judged our ancestors by our standards, it would be extremely dangerous. And the same thing would be true for our descendents looking back and saying, "What were you thinking?" back in the early 21st century.

It's so hard to judge the future in terms of the past. In terms of -- you asked about segregation -- I think if you'd taken my grandmother's era in the early 1900s and she would've looked at the German North Side or even the Italian Third Ward as every bit as foreign as a white suburbanite might thing of the African-American inner city. You know, there was really a strong, strong social barrier between the groups. However, they were all white, so there was as time went on greater possibilities of finding a community of interest.

OMC: Did they work together a bit more than we do, say, in the factories?

JG: Sure, and African-Americans, as well. I mean, they were there at the beginning of the World War I era. ... I think the greatest danger to Milwaukee's welfare and future is that there's a rather massive underclass, largely minority, but not all, and people who may have a high school diploma, or may not, and in my father's day, my grandparents' day, there were family-supporting, sustaining jobs in local industry. The way it seems to me there have been just a few rungs at the bottom of that ladder that have been just ripped out, and where do they begin?

OMC: You have to reach a lot higher to get a foot in, right?

JG: Yeah, and if you have employment rates about 50 percent in the inner city, you know, where's the hope? Where is that generation going to find something that can sustain them and meaning in their lives? And that's all over. That's a major concern. So, manufacturing has certainly taken huge hits in the last 25 years -- since the early ‘80s.

OMC: How will they see us? What will they think of us? Do you think they'll look back to 2009 and think it was a happy place with a great social scene -- sure the economy wasn't great, but, we made the best of it.

JG: That's a good question. We certainly screwed some things up, but I hope they'll look back ... you got me Bobby. If you had, even 20-25 years ago, said you'd have lines outside Downtown nightclubs waiting to get in, you know back in the ‘70s, Downtown was pretty moribund.

So, if somebody 25-30 years ago had said the Third Ward would have these half-million dollar condos, they'd say nah, never happen. Certainly you're on the track with what you know and the past, but that certainly is nothing. It has a formative impact, but not a determinative impact. I would hope that our descendents look at things like the Riverwalk, the cultural theme park development around the Calatrava, Summerfest, efforts to clean up the lake, efforts to turn the Upper Milwaukee River into Central Park, a more green ethic.

I would hope that time that will by definition there'll be fewer resources than there are now that they'll look back and say, "Yeah, they began to get it" and understand that this is something that we have to try to sustain. So I think there have been a lot of hopeful developments that people of the future will look back on and say, "The Riverwalk. It's rediscovering your Downtown." Those are good things.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press. A fifth collects Urban Spelunking articles about breweries and maltsters.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has been heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.