Listen to the Urban Spelunking Audio Stories on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee.

A few years ago I was lucky enough to walk the tunnel that connects the St. Joseph Convent complex to related and once-related buildings to the west, including the former St. Mary’s Hill Hospital, 1445 S. 32nd St., which sits perched atop a hill that fills an entire city block, surrounded by a fence.

During that visit, we didn’t make it as far as the former hospital, because the tunnel was walled off in the middle of 32nd Street when Seeds of Change purchased the building in 1996.

Little did I realize back then the treasures that would await when I would finally make it to the building on the hill.

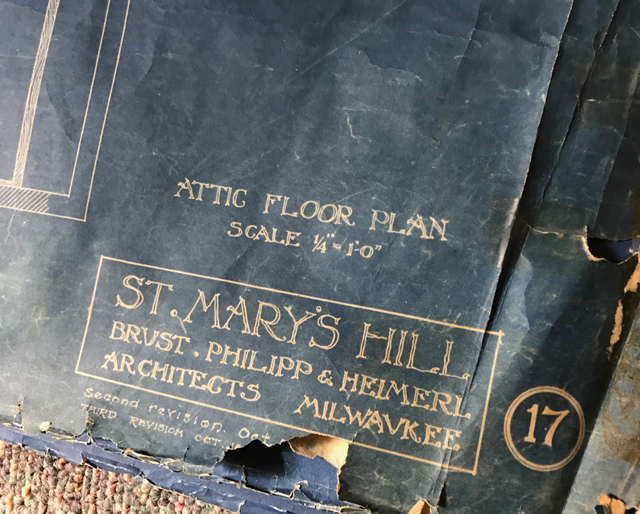

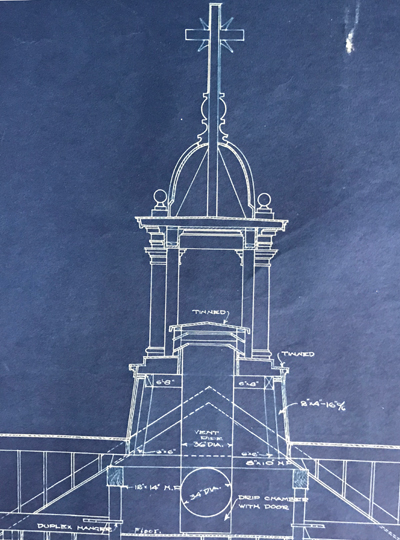

Built in 1912 to designs by Brust, Philipp and Heimerl, the imposing neoclassical building looks much taller than its four stories thanks to its siting atop what is surely one of the highest points in town.

The appropriately named St. Mary’s Hill Hospital was tasked with caring for mentally ill patients and those struggling with drug addiction and alcoholism. It operated there until 1977, when it moved up to Northpoint to join the rest of the St. Mary’s Hospital and it remained in a 1950s-era building at 2350 N. Lake Dr. until 1991 it was folded into St. Mary’s new Comprehensive Counseling Services.

The building was staffed in part by nuns from the School Sisters of St. Francis, whose convent was on Layton Boulevard. Hence the tunnel.

These days, the front of the lower level of the building is home to Seeds of Health’s WIC nutrition program from women, infants and children. The upper floors are home to Seeds of Health’s Windlake school program. The top floor is used for storage.

Sadly, most of the references to the hospital in newspapers over the years are in death notices for patients, though one especially interesting tidbit stands out.

In 1962, the building’s engineer was presented an award for his 50 years of service at St. Mary’s Hill Hospital, which meant he’d been there since it opened.

His name was John Swoboda and he appeared in the paper a dozen years earlier, when, for $50,000, he sold his 50-acre South Side farm to Alverno College – then located in the Layton Boulevard complex just a tunnel’s walk away – which built a new campus on the site. That, of course, is the Alverno we know today.

Though the floor plan of the lower level is basically the same as it was in its early days, the spaces that were once massage rooms and operating rooms and "douche rooms" and waiting rooms are now renovated offices and meeting rooms.

A basement sink.

In the back there is a maze of basement rooms and we set off to try and find rooms we found on the blueprints, including one that served as vegetable storage (and had a built-in potato parer, coffee mill and ice cream freezer), another that was a bread bakery, and yet another that was a steam room.

Down here we took a corridor that led into an addition to the south (pictured above) of the building that was originally an engineer’s apartment (Swoboda’s house?!) and later a daycare, though when I visited it was vacant.

It is also down here that we entered the relatively short section of tunnel that belongs to this building. When the sisters sold the former hospital, a wall was built to block off the tunnel under South 32nd Street, leaving the vast majority of the underground passage to the east of the wall.

From the hospital to the wall is perhaps a 60-second walk each way.

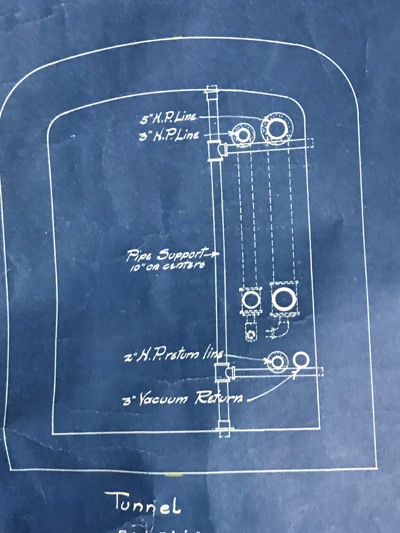

Unsurprisingly, it looks exactly like the tunnel on the other side of the wall. Just a tad taller than six feet and about five feet wide, there are some pipes running along the side.

But there’s very little wildlife to be seen or heard down here. There’s not likely much for them to eat.

The next three floors were mostly patient rooms and wards and these have been converted for use by the school.

Some walls were removed to create classrooms, the floors were carpeted and the ceilings dropped. Other than an area where you can see the location of a former nurses’ station and a dumb waiter that runs the height of the building, there’s little here to suggest the history of the building.

The dumb waiter on the outside and on the inside.

The one really interesting feature on these floors is the two-story chapel, which has stained glass windows, a clock with crosses instead of numbers, decorative plasterwork, a sacristy with handsome wooden built-ins and a balcony accessed from the floor above.

The top floor, below that roof and behind the dormers you can see dotting the exterior, is the least touched. Original trim and woodwork survives, as do hand-painted signs and enamel numbers on the doors.

Also up here is the former assembly hall, which offers access to two small outdoor areas for patients that are caged in. The views are wonderful – you can see Downtown, the stadium and beyond – but the heavy-woven metal screen was surely unpleasant for patients to face.

There’s a cool doorway, too, that leads into a half-height attic space that reminded me of the mysterious space in the film "Being John Malkovich."

Down a long corridor of small offices there is one that is packed with rolls of paper. Unfurling some, we find the original blueprints for the building, plus countless others for additions, alterations and other work. It’s a real trove of history and one could spend days looking at them all.

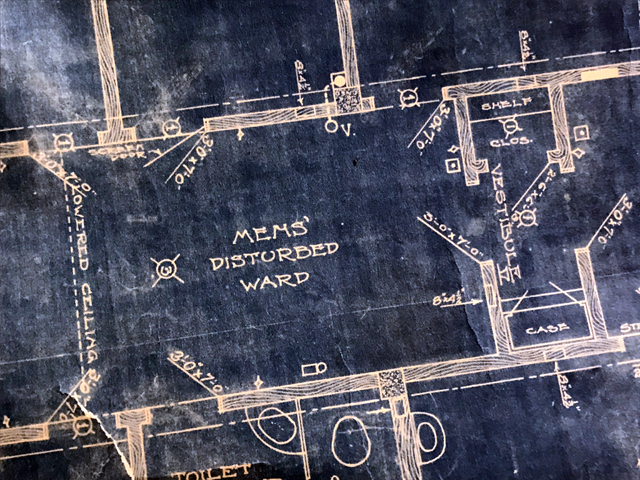

But the ones that struck me most showed the locations of the men’s and women’s "disturbed" wards. Two of my immigrant great-grandparents were diagnosed with schizophrenia relatively young in the 1920s and spent the remaining decades of their lives in places like St. Mary’s Hill Hospital.

Though I can’t say I met the apparitions said to inhabit the place, I arrived with ghosts of my own and they were unleashed at the sight of these words, making this building come alive for me.

I felt the sorrow and the pain and those were further inflated when, in another office, we found a large brown envelope full of x-rays of an unnamed patient. A person, a human being, with hopes, dreams, loved ones, condemned to a life behind these walls. A person like my great-grandparents.

That made it all the more special to me to hear about how the building became – instead of a place of doom, of dread and of dead ends – a place of learning, of new horizons, of bright futures.

Chartered by UW-Milwaukee, Windlake Academy had about 250 students in grades four through eight when I visited. It is part of the Seeds of Health network, whose schools have occupied buildings I've written about on South 1st Street, on Walnut Street and on State Street. Some of the schools in the network have been chartered by MPS.

"I love being in this building," said Theresa Yurk, who was the school principal at the time. "As a former social studies teacher the history intrigues me and I enjoy the connection to historical Milwaukee. The fact that we are up on hill provides us with amazing views and a beautiful setting for a school. The building is a source of pride for us at Windlake Academy."

Yurk said that although the students didn’t really study the history of the building, its past does occasionally pop up at Windlake Academy.

The slate roof.

Like the teacher who had been inside when St. Mary’s Hill Hospital was open.

"We have one who used to come to visit her aunt, who was a patient here," Yurk said. "Our cafeteria area, that was their cafeteria. She remembers going down there and visiting with her aunt. Now she’s a teacher here. It's kind of weird how everything just comes around circle."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press. A fifth collects Urban Spelunking articles about breweries and maltsters.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has been heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.