OnMilwaukee reruns this story in honor of the 34-year anniversary of the tragic Norman Hotel fire.

It has been 34 years since fire destroyed The Norman apartment building, 634 W. Wisconsin Ave. Many of the former residents are still impacted by the tragic event today, mostly because lives were lost, but also because the massive blaze incinerated a structure that housed a community steeped in personal and artistic freedom.

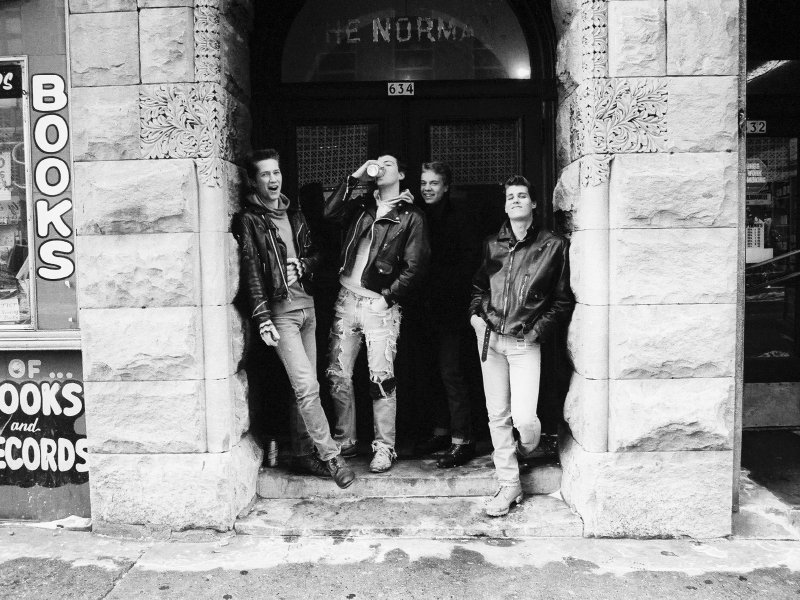

"The Norman was full of drag queens and drug dealers and artists and musicians and dancers. It was a hotbed of alternative lifestyles. It was amazing," says Norman tenant Ricky Becker.

The possibility of a fire at The Norman was predicted – even joked about – for years. It was called a fire trap, a tinder box, and the fact the fire department was located across the street from the once opulent, five-story building became both a source of comfort and irony for residents.

"We knew when we lived there that the place could easily burn down someday," says Keith Brammer, who lived in the mixed-use building "around 1981" with his bandmates from Die Kreuzen.

When The Norman actually did catch fire on Jan. 12, 1991 at approximately 9:30 a.m., neither the predictions of the residents nor the proximity of the fire station could stop the blaze from consuming the building along with the lives of four people and about a dozen pets.

Phyllis Chobot, Margaret Joyner and Joyner’s two children, Fredrico and Nicolas Joyner, were unable to make it out of the building in time and died in the fire.

The fire also destroyed first-floor businesses Alan Preuss Florists, You Light Up My Life (a T-shirt shop), Denmark adult book store and a submarine sandwich shop.

The decrepit building was constructed primarily of wood and featured a massive wooden staircase that stretched up the center of the structure. This was one of the main reasons for the building’s swift flammability.

Warren "Ski" Skonieczny, a now-retired deputy chief of the Milwaukee Fire Department, was among those who fought the five-alarm fire.

"There was an atrium in the center of The Norman from the first floor to the roof – the center was like Lambeau Field and the apartments were like the seats – so when the fire started on the second floor, it created a cyclone up the middle. It created its own storm," says Skonieczny.

Plus, because of the transient nature of the tenants, many of the apartments and hallways were overstuffed with abandoned belongings so there was plenty of fuel to keep the flames blazing.

"It was always my joke that The Norman spontaneously combusted because of all the bad art. There was a lot of it. And some of it was mine," says Norman tenant Stanley Ryan Jones.

The force of the "cyclone" of flames and the gusting winter winds blew pieces of the Norman roof as far away as Bay View. However, the fact it was winter most likely saved other buildings and lives.

"The buildings were close together and the snow on the roofs probably stopped the fire from spreading," says Skonieczny. "But it took six hours to gain control of that fire. We couldn’t do anything until the fire decided it had enough and burned itself out. It did what it wanted to do."

The Norman was built in 1888 as the lavishly appointed Norman Flats. It had five floors featuring 28 units, all of which were constructed with brass fixtures, intricate moldings and fireplaces in each unit – which were later blocked off.

At one point, Miller Brewing Company owned the building and The Norman was a prized property because of its proximity to the celebrated Grand Avenue (now Wisconsin Avenue) theaters, clubs and restaurants.

By the 1970s, however, the west end of Downtown became less reputable with strip clubs, boarded buildings, the adult bookstore, a gay bath house and a 24-hour Dunkin’ Donuts – referred to as "Drunkin’ Donuts" by Norman residents.

"The Norman was run down, but it was old and interesting and beautiful," says Brammer.

Despite the wear and tear of time and Downtown’s struggle to remain vibrant, The Norman remained an eclectic building. It was home to successful and starving artists, families, musicians, sex workers, junkies and the elderly, mostly because of the low rent (about $225-$350 a month) and large apartments.

The Norman represented counterculture at both its worst and its best.

There was a woman who wore a snake around her neck named Fluffy, an impressive collection of sex workers’ spent condoms in the rear stairwell and so many cockroaches they became the subjects of art projects.

"It was very communal. People moved in, people moved on," says Mike Podolak, who lived in The Norman for roughly four years in the early ‘80s. "We were all fledgling punk rockers and alcoholics. It was a weird scene. You never knew what you were going to find when you came back home. I’m almost sure my closet was the portal to Hell."

Jones, an artist and photographer, lived in The Norman from 1987 until the fire.

"The Norman had a faded elegance, a Chelsea hotel movie set feel to it," he says.

Jones moved into The Norman after he was injured as a U.S. Forest Service firefighter / smoke jumper in the western states.

The irony of the fact he was on disability from a firefighting incident at the time of The Norman fire is not lost on Jones. In fact, it almost worked against him. Because of his fire fighting background, Jones says he was briefly a suspect.

"The investigators were keen on me because firefighters sometimes start fires. They may or may not be pyromaniacs – they might just want the extra work – but eventually they realized I wasn’t their guy," says Jones.

On the morning of the fire, Jones was at the apartment of his girlfriend, who lived next door in the building. Suddenly, Jones heard someone yell, "fire!"

Jones threw on a pair of pants, ran into the hallway, broke the glass encasing a fire extinguisher and sprayed a couch burning in the hallway. Flames were already spreading up the wall and onto the ceiling.

Jones, who was not wearing shoes or a shirt, quickly realized the fire was beyond stopping or controlling and so he ran to his apartment to grab a few items and make sure his girlfriend escaped.

He located his camera bag and a plastic zebra print bag filled with photos, but the glass above the door exploded. Jones knew it was time to get out.

He ran out the back of the building where he found himself face-to-face with a fireman struggling with a wooden ladder. Jones set down his bags to assist the firefighter who was trying to rescue another resident, Guy Roeseler, hanging from a second floor window that was billowing black smoke.

Becker observed this interaction from the ground. He remembers Roeseler handing the firefighter a "wiggly pillow case" before climbing out of the window.

"His cat, Mr. Legolas, was in that pillowcase," says Becker.

After assisting the fireman, Jones turned back and realized his camera bag was gone, but luckily, his portfolio bag was still on the ground. He grabbed his photos and walked across the street.

"I remember standing there, across the street from the fire, and thinking it was really a pretty fire. There was such a gray sky that day and the flames were really dramatic against it. It was really quite sublime," says Jones.

Becker lived in The Norman in two different apartments from 1987 until the fire.

"I had just graduated from UWM and I was in the process of doing a performance art / fashion show," says Becker, who was 27 at the time.

The show was only a week away and Becker’s apartment was filled with clothing and costumes, much of which he had designed or silk screened.

"I had just taken a shower, and I heard a sound like a train and then a ‘pop,’" says Becker.

Suddenly, his closet door flew open and a "black, sparking cloud" came flying out. It immediately started a 1940s wedding dress art piece on fire and, within seconds, the room was in flames.

"I was buck naked," says Becker. "It happened so fast. I realized there was no way to get out of my room."

Becker leaped through the flames and ran down the hallway where his roommate, Danielle, was sleeping. He started yelling she needed to get out of the apartment.

"‘Ricky,’ she said, half awake, ‘you’re naked,’" he says.

Becker ran to another floor to make sure people were making it out safely and he found his friend, Susan B. Melin, who passed away a few years ago, coming out of her apartment with her cat carrier. She was wearing a bathrobe and her hair was completely burned off on one side of her head.

She told him one of her walls exploded and she couldn’t find her other cat. Then paused and said, "Ricky, you’re naked."

From there Becker went to the third floor where he found a sweater on a chair in the hallway. He wrapped it around his waist and ran out of the building onto the back porch and scrambled down the stairs and into the Dunkin’ Donuts.

"Unfortunately, they kicked me out because I wasn’t wearing shoes," says Becker. "It was their policy. You had to have a shirt and shoes. I had neither."

So Becker ran to Jim’s Time Out (now Stella's), 746 N. James Lovell St.

"That’s when I freaked out. I started smoking that day. I had never smoked before and suddenly I was smoking three cigarettes at once. People were walking up to me and handing me money and I was saying, ‘Thank you but I have nowhere to put it,’" he says.

Eventually, a man in the bar took off his socks and long underwear and gave them to Becker.

"I lost everything that day – my entire portfolio, antiques. But I shouldn’t complain. I ran out with my life," says Becker, choking up.

Roeseler and his partner at the time, Don Sefton, moved into The Norman in 1986. The couple was known among neighbors for having the most attractive apartment in the building.

"It was a beautiful apartment with 12-foot, vaulted ceilings. We painted the floors cream and the walls jungle green and school bus yellow and dark rose," says Roeseler.

The couple split up about six months before the fire and Sefton moved to the fifth floor.

On the morning of the fire, Sefton was reading a cookbook on his couch in his boxer shorts when he heard Jones yelling and pounding on doors in the hallway. Before he could walk from the couch to the door smoke started pouring into the apartment.

Sefton ran back to the bedrooms and woke up his roommate and new boyfriend. Within minutes, the entire apartment was filled with smoke, so they climbed onto the balcony, where they quickly realized the fire had consumed the back steps. Forced back into the apartment, they ran into a bedroom and climbed out a window onto the roof of the apartment building next door.

"If you weren’t out in a couple of minutes, you were dead," says Sefton, who was forced to leave behind two cats, Lena and Jimmy.

Once outside, Sefton could see his neighbors huddled in front of the Dunkin' Donuts.

"And then I saw Ricky, wearing nothing," he says.

Windows exploded, a woman ran out of the building with a parrot cage. And suddenly, Sefton realized he had not seen Roeseler and started yelling, "Where’s Guy? Has anyone seen Guy?"

Another resident said they saw him inside an ambulance and at that very moment, Sefton saw an ambulance turn on its lights and siren and speed off down the street.

"We were broken up, but I still cared for him," says Sefton.

Three weeks prior to the fire, Norman resident Jimmy von Milwaukee, an artist and gallery owner who ran for mayor, threw a New Year’s Eve party in the building. He made invites and called it "The Last Blue Moon Party."

"It was a beautiful party," he says."Little did I know it was really going to be a ‘last.’"

Von Milwaukee had slept at a friend’s place and was still there the morning the fire broke out. He lost all of his belongings and his cat, Larry, in the fire.

"For a year, I kept beating myself up that I didn’t get the cat out," he says.

Like Sefton, von Milwaukee was emotionally scarred from the blaze.

"I had a lot of anger. I did a lot of drinking. I said I was never going to live with poor people again," he says.

After the fire, most of the residents were not allowed back inside the building, so Jones dressed in what a friend called "construction worker drag" and inconspicuously went into the building with a large gym bag to retrieve some of his personal belongings, photos and slides.

Among the things he recovered was a stack of photos printed on cheap, plastic-coated paper used primarily for proof sheets.

The photos – mostly of the Milwaukee music scene and national acts like David Byrne, Iggy Pop and The Ramones – had melted into a brick-like mass, but Jones soaked them in water and was able to peel them apart revealing completely new images. He later donated 83 of these photos to the Milwaukee Art Museum where they remain in the permanent collection.

After the fire, there were benefits and fundraisers for the residents, most of whom did not have rental insurance, including one at the now-defunct Cafe Melange.

"Unfortunately, someone stole the money before the night’s end," says Jones. "But aside from that, there was an outpouring of goodwill and everyone donated tons of stuff. All of the dumb stuff was back instantly. Suddenly I had sheets, towels, three old TVs."

There were numerous post-fire meetings with the police and firefighters and insurance investigators, but the residents never received any solid information as to exactly how or why the fire started. Some believed it was because of old wiring, others are certain it was arson.

"It was all very suspicious," says Jones. "Most of us felt this way."

Wisconsin law closes the public record on cases after seven years. Consequently, documents pertaining to The Norman fire are no longer available.

"Unfortunately, because of the number of years that have passed since the incident, we don’t have any records available that include a disposition," says Milwaukee Police Lieutenant Mark Stanmeyer.

However, a couple of years after the fire, when the case was still open, Jones obtained a report that declared the fire to be of an undetermined origin and cause.

"Somebody got away with murder," says von Milwaukee.

Skonieczny reported the fire started on the second floor, an important detail that was confirmed by Jones.

"I saw it spread before my very eyes. It started to climb the wall. I knew we all had to get the f*ck out," Jones says.

Although Jones lost almost all of his belongings, it was not the focus of his post-fire grief.

"You might miss this or that, but when people die you can’t get too emotional about your appliances. Not even the family photo album," says Jones.

Becker shared similar post-fire sentiments. He also still suffers from the loss of his neighbors.

"Phyllis and Dorothy lived next door to me at The Norman. We called them ‘Pete and Repeat’ because whatever Dorothy said, Phyllis would repeat it," says Becker. "Phyllis was always very nervous and afraid. She must have been terrified during the fire."

Becker moved to New York in 1994 where he now owns a vintage clothing business called Spooky Boutique. He plans to move back to Milwaukee’s North Side in January, however, to spend more time with his mother.

The fire changed Becker's life and it's one of his primary reasons for leaving Milwaukee. But he realized he couldn't move far enough to escape it.

"Anytime I smell fire, it freaks me out," says Becker. "I think I still have some PTSD. When I first moved to New York, my roommate fell asleep smoking in bed and the place filled up with smoke and I totally freaked out. I know how quickly it can all go up in flames."

After the fire, Roeseler moved to Seattle, and in 1992, Sefton had saved enough money from working at The Coffee Trader and the Hyatt, and he moved there, too.

Roeseler, after living in Hawaii, moved back to Milwaukee with his partner to open Ono Kine Grindz, 7215 W. North Ave. The Hawaiian eatery suffered a minor fire in 2012.

Sefton continued to suffer from PTSD and would cry uncontrollably every time he heard a fire truck's siren, remembering the fear and anguish he felt that January morning.

In 2009, Sefton decided he was going to find closure. So, on the anniversary of Sept. 11, Sefton reached out to local firefighters and offered to make them dinner.

He brought them steak, salad and dessert. He’s done this repeatedly since.

"It has helped me tremendously," says Sefton, who married his partner in 2013. "It’s my homage to firemen. In a small way, I’m thanking those people for everything they do and it has totally transformed the PTSD."

Sefton says he still has uneasy feelings when he hears a siren, but it’s much better. And he has started to recognize what the tragedy taught him about starting over and not being overly attached to material items.

"As I look back, I try to find an element of comfort in that there is something cathartic about letting go of everything," he says.

Within a week after the fire, Jones rented a place on Milwaukee’s South Side and he later bought a house a couple blocks away. "That was one of the only good things about the fire. It was the impetus for me to buy my house," he says.

However, to this day, Jones says he sees his life in two stages: before the fire and after the fire.

"It was a very traumatic event," he says. "It was the fire of the season."

Molly Snyder started writing and publishing her work at the age 10, when her community newspaper printed her poem, "The Unicorn.” Since then, she's expanded beyond the subject of mythical creatures and written in many different mediums but, nearest and dearest to her heart, thousands of articles for OnMilwaukee.

Molly is a regular contributor to FOX6 News and numerous radio stations as well as the co-host of "Dandelions: A Podcast For Women.” She's received five Milwaukee Press Club Awards, served as the Pfister Narrator and is the Wisconsin State Fair’s Celebrity Cream Puff Eating Champion of 2019.