Most Wednesday nights during the summer, there’s music in the park on the west side.

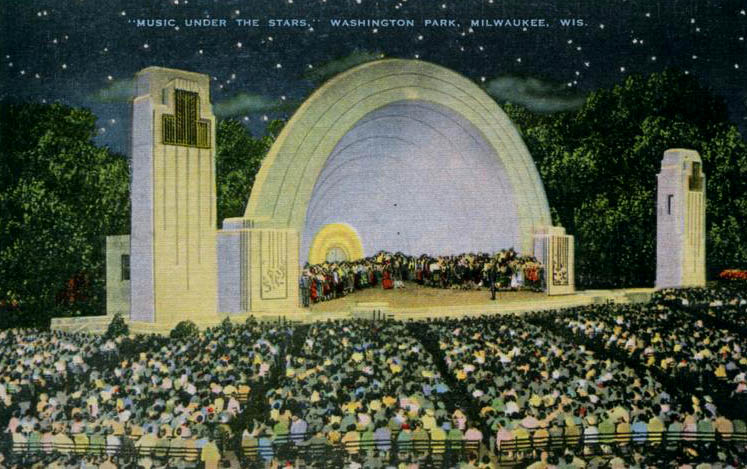

To be more specific, there’s music in the beautiful art deco bandshell in Washington Park, thanks to a series curated by Washington Park Neighbors, which for the past four years has rekindled a longstanding tradition in the park, one that embraces live music to build community.

Free summer music in the park. (PHOTO: Washington Park Wednesdays)

The park was designed – like Lake and Riverside Parks on the East Side – by the master of American landscape architecture Frederick Law Olmsted.

Though best known for the stunning, naturalistic landscapes of Central and Prospect Parks in New York City, Olmsted’s signature is written all over parks across the United States in cities like Milwaukee, where in addition to the three parks, Olmsted designed Newberry and Washington Boulevard.

Washington Park – originally named West Park in 1891 and expanded into the 1920s – was home to the county’s zoo, which was, for many years, its most visited attraction, before relocating to its current home in the early 1960s.

There was an outdoor dance pavilion, too, and in the late 1930s, an anonymous donor committed the funding to build a Temple of Music in the park, which, at 150 acres, was the city’s largest.

The donor, an aging local industrialist long enamored of classical music, was most surely hoping to keep pushing Milwaukee toward having its own respected symphony orchestra.

For years, it had none, leading other cities – notably Chicago, whose orchestra would later perform a regular series here at The Pabst – to poke fun, according to arts critic Tom Strini, who, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, wrote that there had been "many failed attempts, going back to 1890, to establish an orchestra in Milwaukee.

"Two conductors, Polish immigrant Jerzy Bojanowski and German immigrant Julius Ehrlich, vie for status in the 1930s and '40s. Bojanowski leads a WPA-funded ensemble, and Ehrlich directs a Milwaukee Sinfonietta bankrolled by a group of Milwaukee music lovers. Richard S. Davis, The Journal's legendary music critic, at first touts Bojanowski. He later switches camps to praise Ehrlich and lambaste Bojanowski on a regular basis. Davis sits on the Sinfonietta's board of directors. Journalistic conflict of interest rules were a little lax in those days."

While it’s difficult to say for sure whether we’d have an MSO today without it – and there is no direct line connecting the two – it seems likely that the success of the Washington Park bandshell was surely among the sparks that helped pave the way for a permanent symphony here.

In late 1937, news emerged of the donor and his donation. The papers reported that architect Fitzhugh Scott – who had started out working in the office of Alexander Eschweiler, venturing out on his own in 1914 and notably designing the Allen-Bradley building – had been tapped to design the $65,000 structure.

The new bandshell was to replace an earlier, much smaller, almost gazebo-like octagonal bandstand built, according to Carlen Hatala of the city’s Historic Preservation office, during 1896-97 to plans drawn by architect Howland Russel.

The original bandstand. (PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library)

"The bandstand had open sided walls and the base consisted of split boulders," wrote Hatala in a historic designation study report on the park. "The grounds around this bandstand were referred to as the concert grove. Free open-air concerts were being held in a number of the parks and proved very popular. Washington Park was among the parks to feature concerts.

"Private subscriptions were raised at various times specifically to fund the concerts at Washington Park. Performances were provided by local musicians and such groups as the Milwaukee Musical Society. Some 10,000 people were said to have attended in 1898. A photograph of the concert grove with many people sitting on the lawn, was included in the 1905 Annual Report."

In December 1937, architect Scott turned over his plans to be examined by the engineers of the county parks commission, which had taken control of the city and county parks earlier that year.

The bandshell under construction and in 1943. (PHOTOS: Milwaukee Public Library)

By early January 1938, Scott – whose son later took over the firm and trained David Kahler and Thomas Slater, who carry on the business as Kahler Slater – was ready to share the plans – and a pretty cool looking little model – of the project with the public.

The day that contracts were announced with contractors like Selzer-Ornst, who would build the Temple, Scott also announced that the donor was 80-year-old childless widower Emil Blatz, son of Blatz Brewery founder Valentine Blatz.

The Sentinel described the retired Blatz – who had once been a key player in the Second Ward Bank (whose building is now home to the Milwaukee County Historical Society) – as, "long a leading figure in the city’s musical and cultural life. ... he has never lost his love of fine music."

At the same time, the Journal elaborated on the plan, writing, "The band shell is to be at the west end of Washington Park on the Washington Boulevard side (at the time, the freeway was not yet built and that land was part of the park). All contracts have been let and construction is expected to start this week.

"The amphitheater placed in front of the shell will have permanent seats for 10,000 persons ... (and) will be inclined on a 4 degree grade, allowing a full view of the bandshell stage for all seat occupants. Between the amphitheater and the shell will be a large pit for musicians when the stage is being used for operas.

The site of the orchestra pit.

"That part of the bandshell stage in front of the arch will be 100 feet wide and 20 feet deep. The part back of the arch will be semicircular, 60 feet wide at the front and 28 feet deep at the center. The stage is to be large enough, Scott said, to seat 100 musicians or to accommodate even those operas requiring the largest casts. There will be four private dressing rooms on the stage level and two on the ground level."

Work proceeded quickly and by the summer, the bandshell and amphitheater were ready and put to immediate use, with nine concerts drawing 148,000 people that summer.

The penultimate concert of the debut season of what was dubbed "Music Under the Stars" took place on Aug. 23, 1938 and served as the official dedication of the Blatz Temple of Music, which would’ve been packed to the gills, considering there were just under 10,000 permanent seats and space for another 10,000 to be added later.

In fact, reported the Sentinel the next morning, "40,000 concertgoers – the biggest crowd that such a park program has ever drawn – gathered about the new $100,000 Temple of Music to see the gift and the donor, to catch a glimpse of (radio star and singer) Jessica Dragonette – just a blond little doll framed in a huge shell – and to hear her and the (WPA- and County-funded) Wisconsin Symphony Orchestra of 100 players seal the bargain with two hours of song and symphonic music."

But before Dragonette performed, with Jerzy Bojanowski conducting the orchestra, all assembled sang "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Then Blatz was introduced and spoke briefly, saying, "If this temple of music gives you as much pleasure as it has given me in donating it, I am fully repaid."

The architect was introduced, too, and then Lawrence J. Timmerman of the county board officially accepted the Blatz gift on behalf of the people of the county.

Park Commission Chair C.R. Dineen saluted park commission recreational director Don Griffin, who had planned the concert series, and Mayor Daniel Hoan said Blatz would, "rank high in the roll of the great benefactors of Milwaukee."

To that, the Sentinel added, "the donor had done more than give a bandshell to the people – he had presented the opportunity for an amazingly successful revival of summer music and the initiation of a program which may yet bring the city a permanent symphony orchestra."

While it sounded like a marvelous time was had by all, then – as now – someone is always unhappy. A few days later, the morning paper carried a letter from one Alma Johnson Salomon, who wrote to say she enjoyed the music at the dedication of the bandshell, "and the singing of Jeanette (sic) Dragonette. In the past, Milwaukee has not been privileged to hear the music of such an outstanding artist under the stars, which, in itself, provides a setting beyond compare.

"Yet it was very disconcerting when just in the midst of the most beautiful selections there was heard the shriekish wails of the jitterbug musicians (or can you call them musicians), playing in the dance pavilion above the boathouse. To say the least, it was sacrilege, and showed the incompetence of those in charge of arrangements."

And she wasn’t the only one keeping an eye on the so-called "jitterbugs," a term used to describe high-energy dancers of the day. The Journal, too, feared that such joyful and enthusiastic music would mar the young concert series, which it declared to have proved itself "something wholesome."

A 1943 postcard view.

"This attendance has convinced officials that more concerts can be arranged for next year, the paper wrote in September 1938. "There is something subtly desirable about them; something wholesome, that Milwaukee should capture in greatest possible measure. There is another factor about the concerts that has more importance than many folks will see. They were self-sustaining. They were made to pay their way, through purchasers of reserved seat tickets.

"We hope that the county park commission will arrange ever finer concerts next year. We read that at least one of next year’s concert may be arranged for the benefit of ‘jitterbugs.’ Jitterbugs may have their place. Perhaps their demand for clash and bang and primitive rhythms warrants response from someone. We doubt that someone should be the park board. We think that jitterbug syncopation would clash pretty definitely with ‘concerts under the stars’; would disturb violently the atmosphere that the park commission has thus far created."

Regardless of the looming threats of "syncopation" – which to modern ears sounds a whole lot like a thinly veiled reference to black music – the first season was to be celebrated.

In addition to the huge turnouts, NBC carried parts of two of the first season of shows on its red radio network and CBS also broadcast from some, including the Aug. 23 Dragonette performance.

Music Under the Stars, 1947. (PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library)

As 1938 came to a close, the county parks commission released its annual report, noting that the parks’ most popular activity was bathing, attracting 1,576,170 Milwaukeeans, with the Washington Park Zoo coming in second with an attendance of 1,365,520. Thanks to seven flower shows, accounting for about two-thirds of its visitors, the Mitchell Park Conservatory broke its previous attendance record, too.

The report noted that 186,750 attended concerts and operas in the parks in 1938, and considering that 148,000 of those were at just nine Blatz Temple of Music performances, the Journal was right to point out that, "An important addition in 1938 was the Emil Blatz Temple of Music in Washington Park."

Indeed, the Music Under the Stars program would endure for 55 years — and included some performances at Humboldt Park, too — ending in 1992 and garnering national notice for hosting events like the first major appearance of singer Jeanette MacDonald as a concert soloist in 1943, and legendary jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong.

Over the years, the bandshell has hosted many famous names, including Duke Ellington in July 1966, as part of the four-day Old Milwaukee Days celebration, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, and a young senator from Illinois, Barack Obama, in 2004.

After six successful years at County Stadium, the Kool Jazz Festival announced that it would host its 1982 event at the bandshell, drawing opposition from neighbors, who feared traffic and noise. And with good reason, it seems. The festival was so popular at the stadium that in 1978 the freeways were jammed with fans on their way to the show.

Akira Tana, Ron Carter and Percy Heath at the 1982 Kool Jazz Festival.

(PHOTO: Howard Austin, Courtesy of Joey Grihalva)

However, fears were allayed and the bandshell hosted the event with an astonishing lineup, including Herbie Hancock, Ella Fitzgerald, Chico Freeman, Modern Jazz Quartet, Gerry Mulligan, Mel Torme, George Shearing, the Heath Brothers, Spyro Gyra, Oscar Peterson, Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughan and Freddie Hubbard. Related shows held at Peck Pavilion and The Past Theater featured Wild Bill Davison and Ornette Coleman.

But, attendance was terrible. While Aretha Franklin and Natalie Cole drew 43,000 to their shows at the festival at County Stadium, a mere 4,700 came out to see the legendary Ella Fitzgerald at the bandshell.

As noted by the newspaper, what the protestors couldn’t do, the lack of attendance did. Festival organizers decided to skip Milwaukee in future years, ending its run here.

Dead Man's Carnival performing in 2017. (PHOTO: Washington Park Wednesdays)

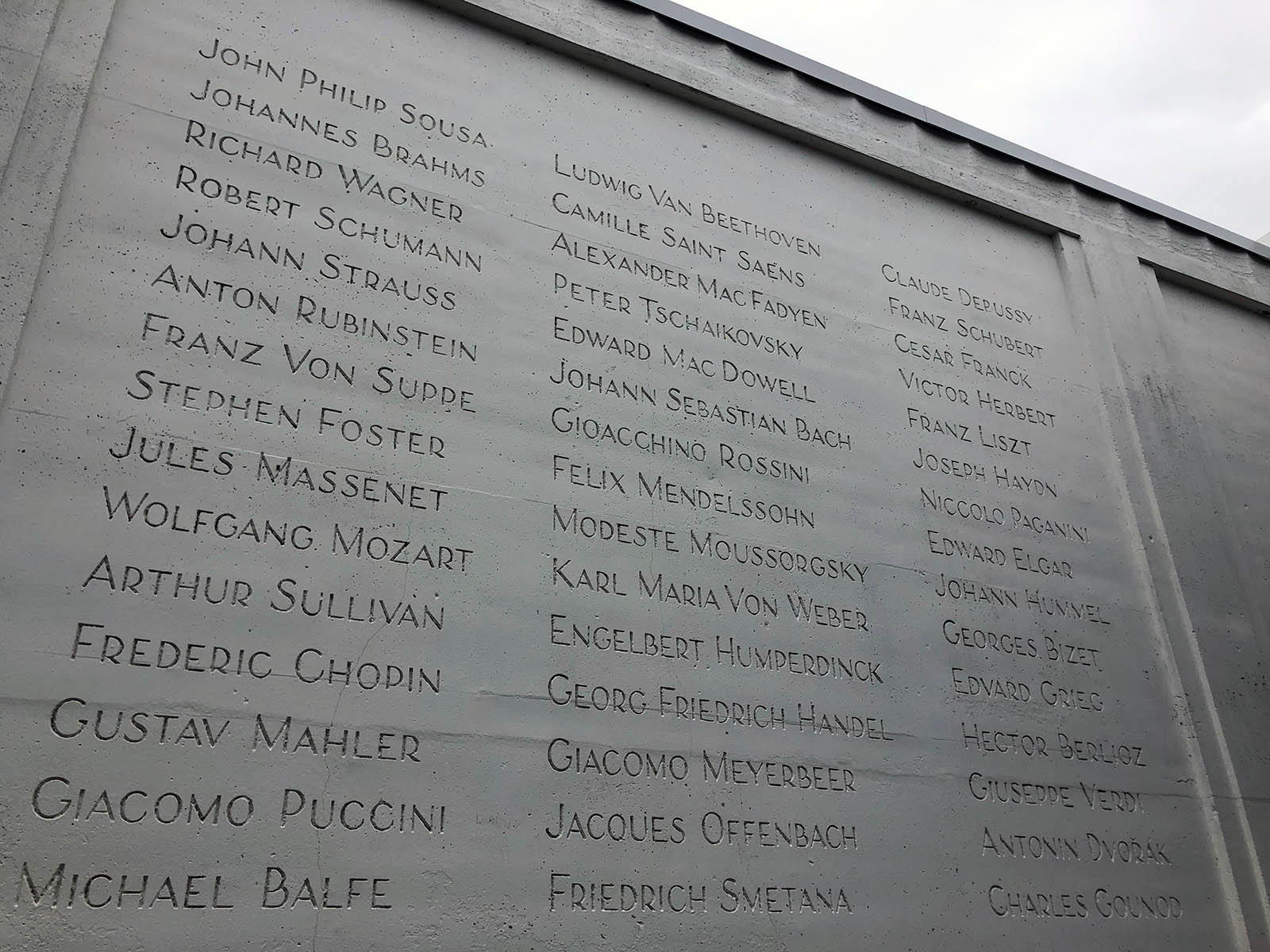

But the music continues thanks to Washington Park Neighbors, and if you go, be sure to check out the commemorative plaques on the east side of the east pylon, the friezes flanking the stage and the list of renowned composers and musicians engraved on the back of the building.

While you’re back there, look up and note how the architecture of the bandshell highlights the science at work. The arched top looks just like a loudspeaker or bullhorn, helping to project the sound from the stage out over the crowd.

Inside, up a short flight of stairs there are a number of small dressing room and other spaces arrayed around a wide passageway that follows the arc of the stage's half-moon shape.

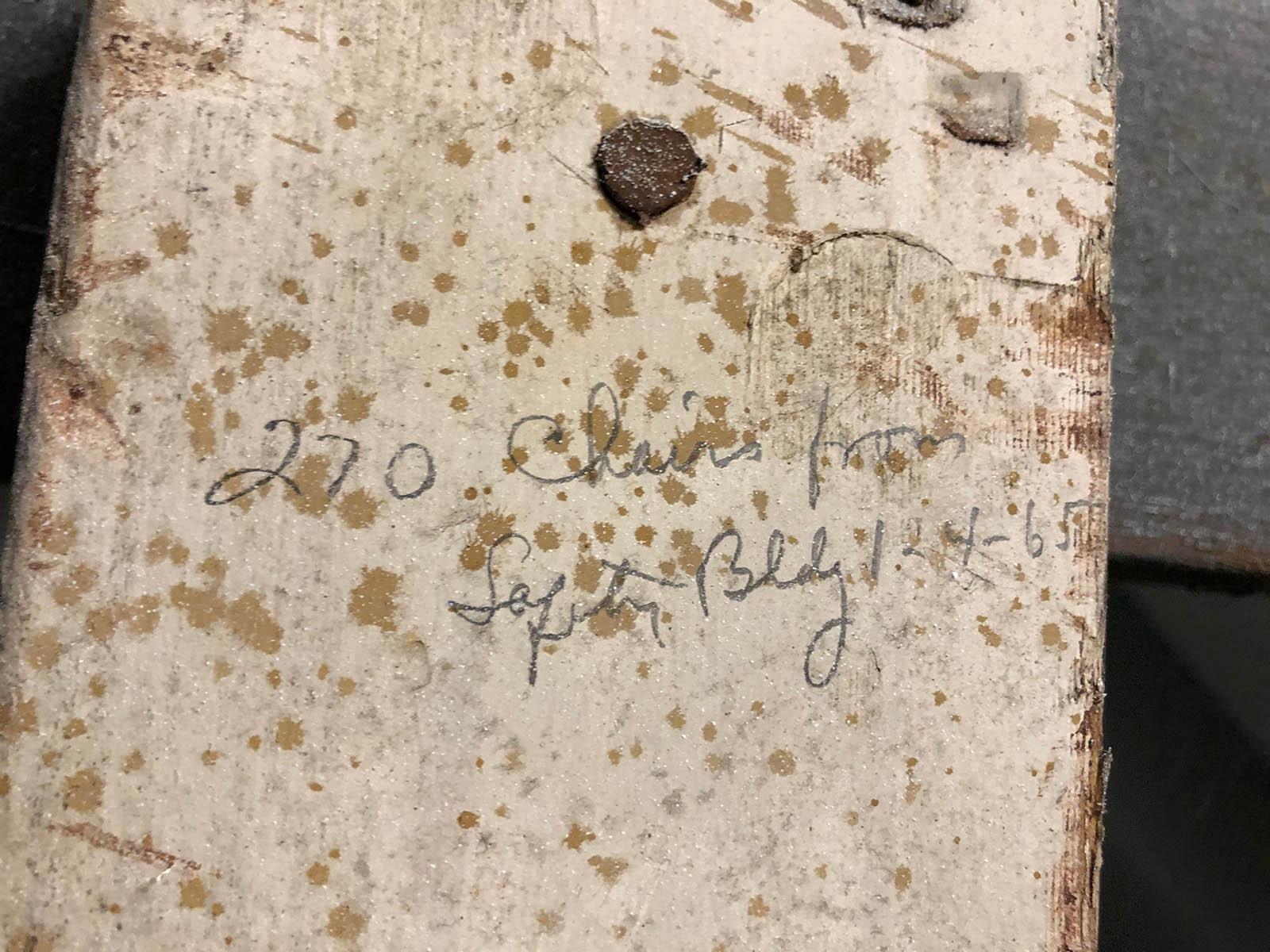

A recent renovation led to new, hopefully vandal-proof doors and a fresh coat of paint, which, sadly, in one room led to the covering of signatures dating as far back as the 1930s, according to Park Unit Coordinator of the Washington Unit Sue Gillman. Only a handful – the oldest from 1965 – seem to have survived.

Gillman takes me downstairs, too, to see a couple very large dressing rooms – perfect for orchestra musicians and theater casts – each with a long row of light bulb sockets along a wall where there surely had once been mirrors and a row of sinks opposite – and a big open space directly beneath the stage.

In that open area there are a couple stairs up to a blocked-up door that led to the orchestra pit in front the stage (pictured below). The pit, which had been covered for a time with plywood, has since been backfilled with gravel and paved over.

There are also some infrastructure rooms, including one upstairs for the audio system and an old electrical room below (pictured below).

Gillman says there was access into the pylons – which may have housed speakers behind the decorative grilles at the tops, but that's unclear – but nowadays they're shut up tight.

Out in the amphitheater these days, there’s bench seating with a large grassy slope for more to sit on blankets, chairs or the grass. It swoops up to the top of the natural depression in which the bandshell was built, to where there’s a bronze sculpture depicting German writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich von Schiller.

The double statue is a recasting of a sculpture by German artist Ernst Friedrich August Rietschel in Weimar, Germany and was a gift to the city in 1908 from German Citizens of Wisconsin. It was rededicated by the German-American Societies of Milwaukee in 1960 when it was moved to its current location to make way for the construction of what is now Highway 175.

Now, they stand in a lovely balance with the bandshell, perhaps keeping watch to make sure the jitterbugs don't take over the Blatz Temple of Music.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press. A fifth collects Urban Spelunking articles about breweries and maltsters.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has been heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.