Do you ever wonder how many cities have a rather centrally located private pet cemetery topped with a public monument by a respected artist, the unveiling of which was attended by the mayor?

Well, we know of one for sure: Milwaukee.

Installed in 1910 at what is roughly 1618 S. 16th St., on a small triangle bounded by Bow Street, Pearl Street and Cesar Chavez Drive, is the Richard D. Whitehead Monument, which has been a neighborhood landmark for 110 years now.

Built initially to function as a water fountain for horses, the fountain has been shut off, but the monument remains.

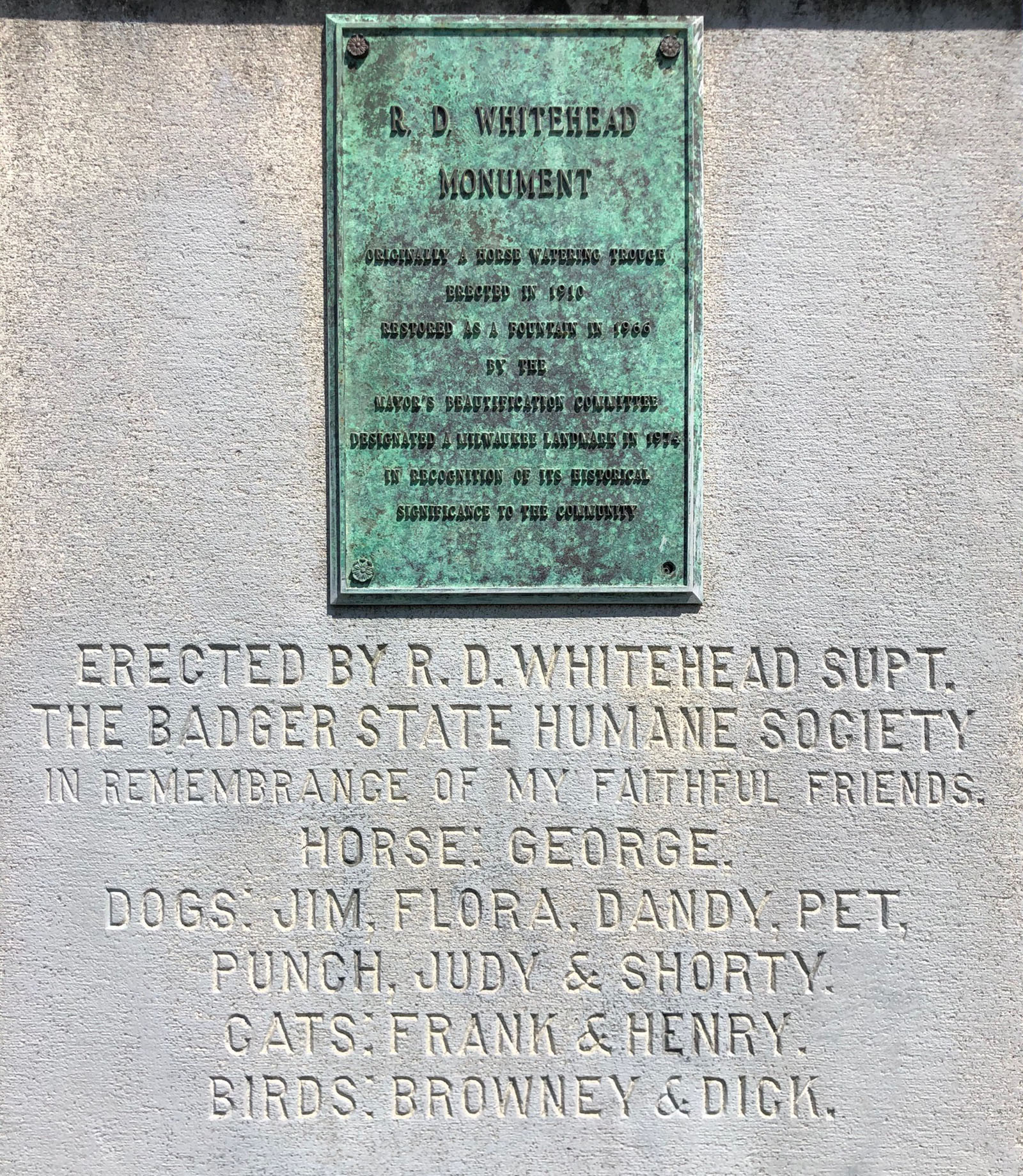

In addition to bronze plaque depicting George the horse and Dandy the dog, this is what’s etched into the granite:

ERECTED BY R. D. WHITEHEAD,

SUPT. THE BADGER STATE HUMANE SOCIETY

IN REMEMBRANCE OF MY FAITHFUL FRIENDS

HORSE: GEORGE

DOGS: JIM, FLORA, DANDY, PET, PUNCH, JUDY & SHORTY

CATS: FRANK & HENRY

BIRDS: BROWNEY & DICK

So, what’s the story?

Well, we have to start with R. D. Whitehead (pictured at right).

Born in 1832 on a farm in Newark, Ohio – the county seat of Licking County, I kid you not – as a young man Richard Demerus Whitehead moved to Chicago and took a series of jobs, including in a livery stable.

By 1879 he’d become interested in the work of the humane society, which had sprung up in Chicago, as in many cities, after Henry Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York in 1866.

Almost immediately, it seems, the directors of the newly formed Wisconsin Humane Society, in the words of the Milwaukee Sentinel, "prevailed upon (Whitehead) to come to Milwaukee and assume charge of the work of the Wisconsin Humane Society."

His pay was to be, according to a history of the humane society, "not more than $1,000 plus the expense of one horse." He was also given police powers so that he could make arrests, something he was expected to do only as a last resort.

"The earnestness and aggressiveness with which the warmhearted Whitehead carried out his duties were soon noted by the board," notes that society history.

That work, however, as you can imagine back then, was not easy. The streets were packed full of horses and city life did not preclude copious numbers of chickens, pigs and other animals, as well as cats and dogs.

"While he met no open opposition," the Sentinel wrote upon his death in 1911, "the support given him was not sufficient to carry out the work as he wished, and during the first years he was obliged to work almost entirely alone, organizing and systematizing matters not only in the city but throughout the state.

"As the years passed, his eagerness and aggressiveness together with the many good results shown for his efforts, interested many of the philanthropic people of the city and the society became more stable and better able to carry out its plans."

After the death of his wife Cynthia in 1905 – and some complaints by "those who were the cause of suffering" for what they called his "unnecessary meddling" – Whitehead split from the Wisconsin Humane Society, which declared the accusations against Whitehead to be baseless.

In 1906, he founded the Badger State Humane Society and worked tirelessly, says the humane society history, "to provide means for the prevention of cruelty to animals, children, women, aged, dependent people and criminals of the State, and to cooperate with other humane agencies."

Newspaper reports of the day list monthly updates, like this one: "The society’s report says that in September 45 persons were assisted, 200 animals were relieved, 25 dogs and cats were given homes or destroyed, and 100 crates of poultry were examined" and "45 people and 210 horses were given relief by the Badger State Humane Society during February. Owners of horses are urged to prevent their animals from coming into contact with salt used for snow melting."

Whitehead was also known for his crusade to end cockfighting in the city.

Interestingly, also not unusual were reports that Whitehead had been given infants as young as a month old by mothers unable to provide care and by folks who found babies abandoned on their doorstep, and that he was making the children available for adoption.

Whitehead was clearly a respected member of society, sometimes called upon by newspapermen for comment after heinous crimes and other incidents. But he was also outspoken, drawing criticism, as in 1908 when former Gov. George Peck publicly chided Whitehead for calling President Theodore Roosevelt, "a coward for indulging in the hunt," in the words the Journal.

Part of Whitehead’s work was the construction of drinking fountains around the city for horses and he was responsible for at least 29 such amenities. Some were organized under the auspices of the Badger State Humane Society – and paid for by public donations – and even more of them were the work of Whitehead alone.

And lest one be confused, Whitehead was primed to speak out in his own defense, as he did in a letter to the editor of the Sentinel in July 1910, regarding the Bow Street fountain, which is now the last remaining horse trough in the city.

"I noticed in the Evening Journal that the Badger State Humane Society is erecting a fountain on the south side," wrote Whitehead. "That is not so. I am erecting a fountain, dedicating it to my animals, with my own money, to cost me something over $2,000. I have with the help of the citizens erected 19 drinking fountains for animals, paid for them with my own certified check, and then begged the money from the citizens to cover all the expense.

"The Bergh fountain (pictured at right) the Wisconsin Humane Society had nothing to do with, except one of the board, a lady, nor would they have anything to do with it until the money was all subscribed, collected and in the bank. The lot at this fountain that I am erecting I tried to buy several years ago to bury pet animals, but did not succeed. The city now owns it and has given it to me to erect this fountain and monument. The society has nothing to do with it."

The Bergh fountain, incidentally, that Whitehead references is the statue with a fountain at the base one that was unveiled in front of City Hall in 1891 and now stands (sans fountain) outside the Wisconsin Humane Society at 4500 W. Wisconsin Ave. It was paid for by $14,000 raised from public donations.

Even those who give their lives over to the service of others can get angry sometimes. And they can be a little quirky.

The fountain in 1910 with, presumably, Whitehead.

The fountain in 1910 with, presumably, Whitehead.

According to an article in the Sentinel on the occasion of the unveiling of the Bow Street fountain, the paper notes that the watering facility will be a monument to Whitehead’s departed pets, who were to be buried beneath it.

It seems that Whitehead had buried them – they’re the ones whose names are engraved in the granite – in white oak coffins that were exhumed and moved to the site. One of them, Jim the dog had died, "about 32 years ago, shortly after his owner came to Milwaukee."

Some might find this a little quirky even today when we seem to be even more enamored of our pets.

George, the horse depicted in the plaque – which also features Dandy the dog – was still alive in 1910 but, Whitehead told the paper, "when George dies, he will also be buried by the monument." Whether or not this occurred I can’t say, but Whitehead died less than a year later, so it’s possible he did not live to see this promise through.

In listing the pets interred beneath the fountain, the Sentinel noted of the dog Shorty that, "Mr. Whitehead says "Shorty’s" father was a monkey." Um, okayyyyyyyy.

The monument was the work of Norwegian-born American scuptor Sigvald Asbjørnsen, who had come to America in 1892 and worked on sculptures for the buildings of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Among his many works include likenesses of Benjamin Franklin in Lincoln Park and Leif Erickson in Humboldt Park in Chicago; figures in the General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument at President’s Park in Washington, D.C.; a bust of explorer Roald Amundsen in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park; and a memorial to composer Edvard Grieg in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

Asbjørnsen likely was responsible only for the brass plaque on the monument, not the granite structure.

When the fountain was officially dedicated on Sept. 6, 1910, it was unveiled by 5-year-old Marjorie Virginia Smith, and Mayor Emil Seidel was on hand, along with other dignitaries.

But because people never change, Whitehead was quickly back in the news defending the fountains against critics who said that the fountains would spread disease among horses.

"I find some criticism about drinking fountains for animals, from people no doubt in ignorance," Whitehead told the Sentinel less than a month after dedicating the monument. "The fact is that of the 20 fountains I have erected in Milwaukee it would be impossible for horses to contract any disease from drinking at them, unless the city shuts the water off, so that it will become stagnant."

This would quickly become irrelevant. As a city historic designation report noted, while, "it was designed to serve the practical purpose of watering the horses of the farm produce wagons, deliverymen and milkmen that passed this then-important intersection on their way to the once-important shopping area on South 16th Street between National and Greenfield Avenues ... it is ironic that it was erected at a time when horse drawn conveyances were already disappearing from Milwaukee’s streets."

Whitehead soon found himself ailing and, the Sentinel reported, "even while confined to bed by his sickness (with a debilitating bout of sciatic rheumatism) he took an active interest in what was being done by the society he headed."

Whitehead died at home on Milwaukee Street in June 1911 and his society would only outlive him by a year.

On his deathbed, Whitehead asked Charles Gettelman and other Badger State Humane Society board members to keep the organization alive and continue his work. But the board was divided on whether to do that or to merge with the Wisconsin Humane Society, of which many were also members.

Some board members said they, "were only interested in the Badger State society because they wished to support Mr. Whitehead, whom they believed to be an earnest worker. These are anxious to unite the two societies."

At the same time, the Wisconsin Humane Society’s Superintendent H. Lieb Phillips believed a merger was inevitable.

Three days after Whitehead was buried at Forest Home Cemetery, the board decided to remain independent in the short term, but in less than a year, the two societies were merged. In the words of the Sentinel, "The Badger Humane Society was taken over by the Wisconsin Humane Society and will hereafter work in conjunction with the Wisconsin society."

The monument was renovated in 1966 and a small fountain was added to the basin. It was designated a city landmark eight years later. The trough fountain has since been converted into a planter.

While his name isn’t especially familiar to today’s Milwaukeeans, it remains etched in one of the most unique monuments around town and one that should serve to remind us all to be kind to our four-legged friends.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press. A fifth collects Urban Spelunking articles about breweries and maltsters.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has been heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.

%20copy.jpg)